Shifting Cultivation is a traditional method of cultivating food grains in jungles and steep hillsides, especially in northeast India.

Imagine this: Have you ever wondered how farmers grow crops in dense jungles or on steep hillsides? Forget tractors and plows! Shifting Cultivation, also known as slash-and-burn agriculture, is a fascinating method that’s been around for centuries. A farmer plants crops on a patch of cleared land, and then the land “rests” for years while the forest grows back.

✳️ Explore All Indian Geography Notes

These detailed notes will explore all the critical aspects of shifting Cultivation. This includes understanding the various names associated with shifting Cultivation, its advantages and disadvantages, environmental impacts, farming methods, and types, and case studies on shifting agriculture in Nagaland.

The Relevance of Shifting Cultivation in Exams👇

Shifting Cultivation is also essential for almost all government exams like SSC, UPSC, RRB NTPC, and all other regional-level exams. The native name and some critical facts about Shifting Cultivation are always asked in various competitive exams.

Here is an example for You. Try This

Question: What is shifting cultivation called in Malaysia?

A. Ladang

B. Jhum

C. Milpa

D. Ray

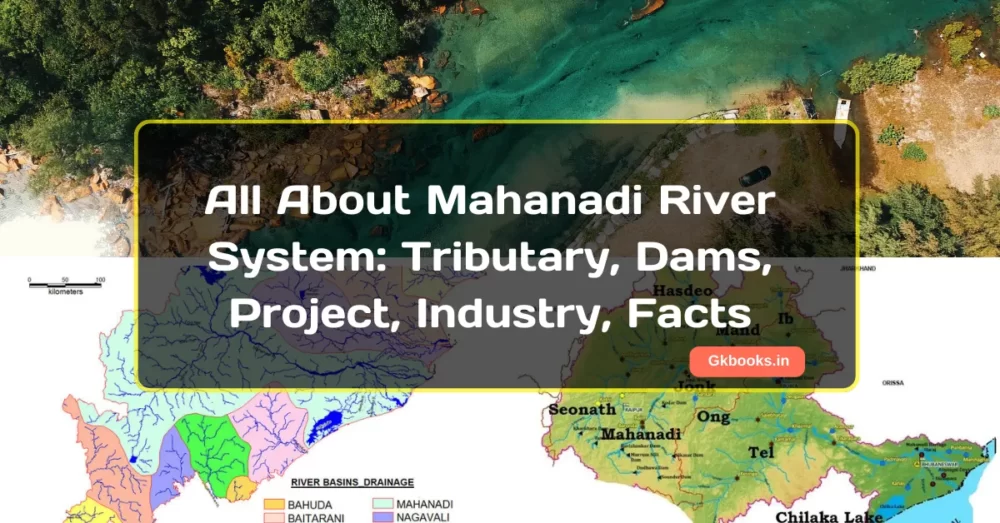

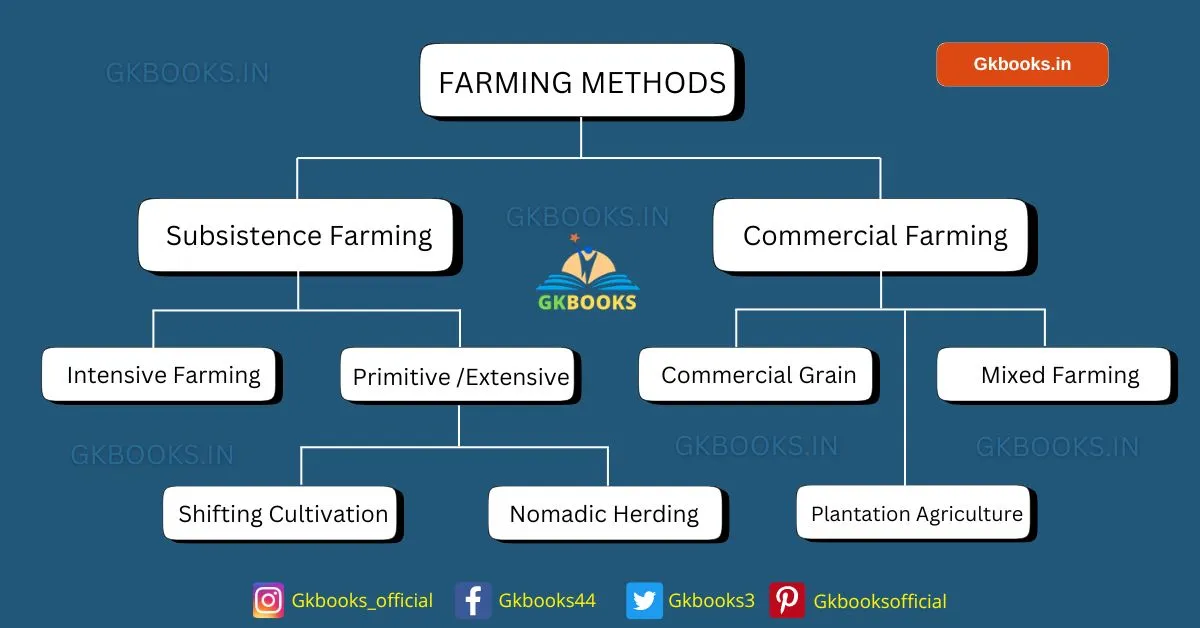

Types of Agriculture by Farming Methods

Before we proceed to discuss shifting cultivation, let’s first explore the types of farming. There are two main categories of agriculture based on how farmers grow crops and raise animals:

1. Subsistence Agriculture

- Farmers grow crops and raise livestock mainly to feed themselves and their families, with little or no surplus left over to sell.

- This can be further divided into two types:

Primitive Subsistence Agriculture (Shifting Cultivation)

- Shifting cultivation is an extensive practice. This means that it uses a large amount of land to produce a relatively small amount of crops.

- Also called slash and burn agriculture.

- Farmers clear a patch of forest, burn the remaining vegetation to fertilize the soil, and plant crops for a few years.

- Once the soil loses its fertility, they move on to clear a new area and repeat the process.

Intensive Subsistence Agriculture

- Farmers use small plots of land intensively to produce as much food as possible for their families.

- They often rely on manual labor and traditional tools.

2. Commercial Farming (Cash Crop)

Commercial Farming is a large-scale farming system focused on growing a single cash crop for commercial purposes. Here’s a breakdown:

- Large-scale: Plantations cover vast areas of land, often hundreds or even thousands of acres.

- Monoculture: A single crop, like coffee, cocoa, sugarcane, or rubber, dominates the plantation.

- Commercial focus: The main goal is to generate profit by selling the harvest in national or international markets.

- Labor: Traditionally, plantations relied heavily on hired labor, which sometimes involved unfair practices in the past.

Types of agriculture in a Nutshell

Here’s a table representing various types of agriculture based on farming methods:

| Type of Agriculture | Description |

|---|---|

| Subsistence Agriculture | Farming primarily for self-sufficiency, where the produce is mainly consumed by the farmer and their family. |

| Commercial Agriculture | Farming with the primary goal of selling produce for profit, often on a large scale. |

| Intensive Agriculture | Farming involving high levels of input (e.g., labor, machinery, fertilizers) per unit area of land. |

| Extensive Agriculture | Farming characterized by low levels of input per unit area, typically practiced on large land holdings. |

| Organic Agriculture | Farming without the use of synthetic chemicals, relying instead on natural methods of pest and weed control. |

| Precision Agriculture | Farming using technology (e.g., GPS, sensors) to optimize inputs such as water, fertilizer, and pesticides. |

| Mixed Farming | Farming involving the combination of crops and livestock, often with the aim of maximizing resource utilization. |

| Agroforestry | Farming that incorporates trees and shrubs into agricultural systems, providing multiple outputs. |

What is Shifting Cultivation?

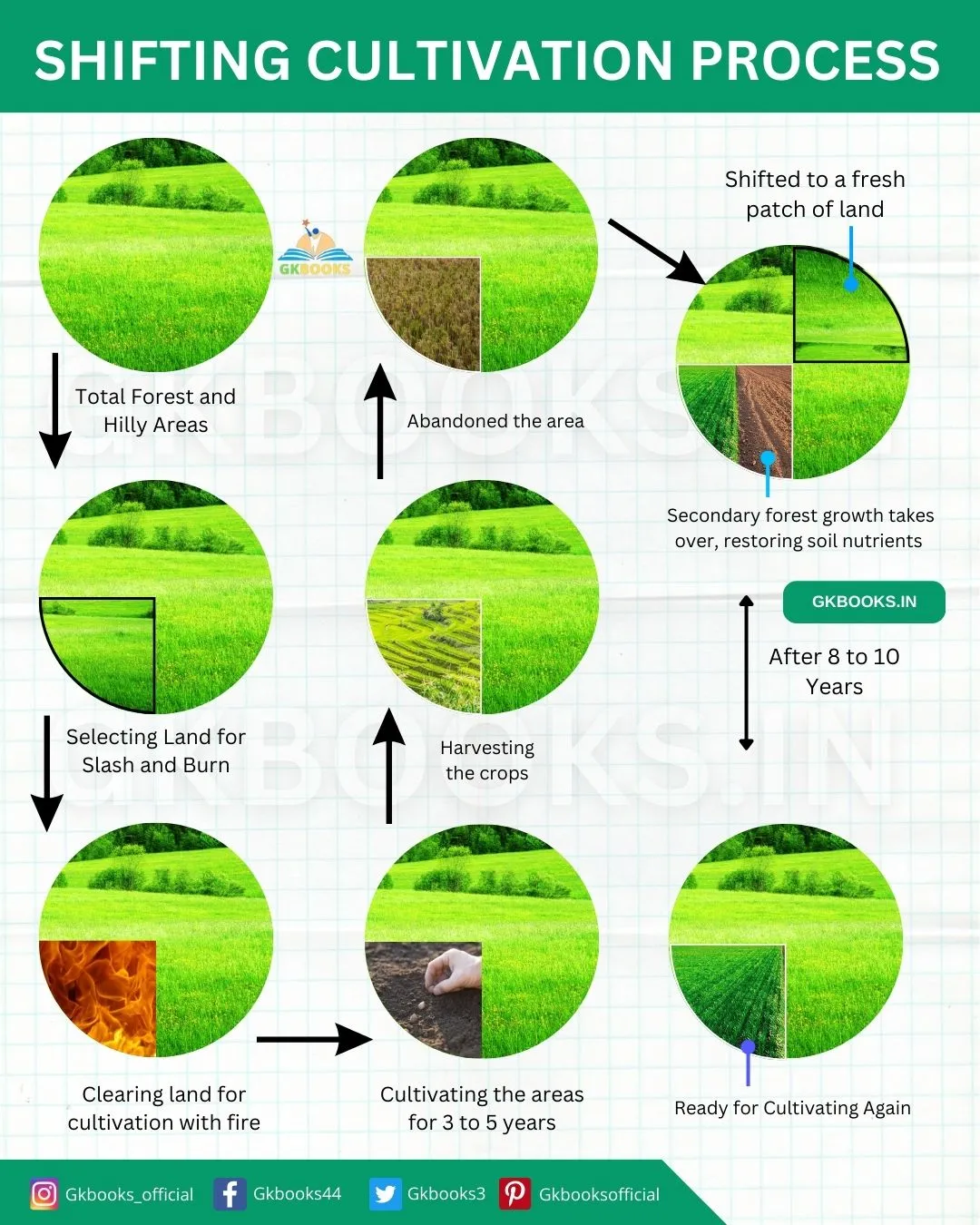

Shifting Cultivation is a form of primitive subsistence agriculture in which farmers clear a small area of land and cultivate food grains like cereals and paddy.

After harvesting the crops, when the fertility of the soil decreased, they abandoned the area and shifted to a fresh patch of land.

Shifting Cultivation is also called slash-and-burn agriculture because the natural vegetation of the small land area is usually cleared by fire. The ash produced by burning natural vegetation helps in increasing the fertility of this soil.

In shifting Cultivation, farming is done with very primitive tools such as sticks and hoes.

After 3 to 5 years of Cultivation, the soil loses its fertility, and the farmers move to other places and clear another patch of land to start farming again. The farmer then shifts to different parts and clears another patch of the forest.

In the table below, we have listed the important names of slash-and-burn agriculture or shifting cultivation in Indian states and other countries around the world.

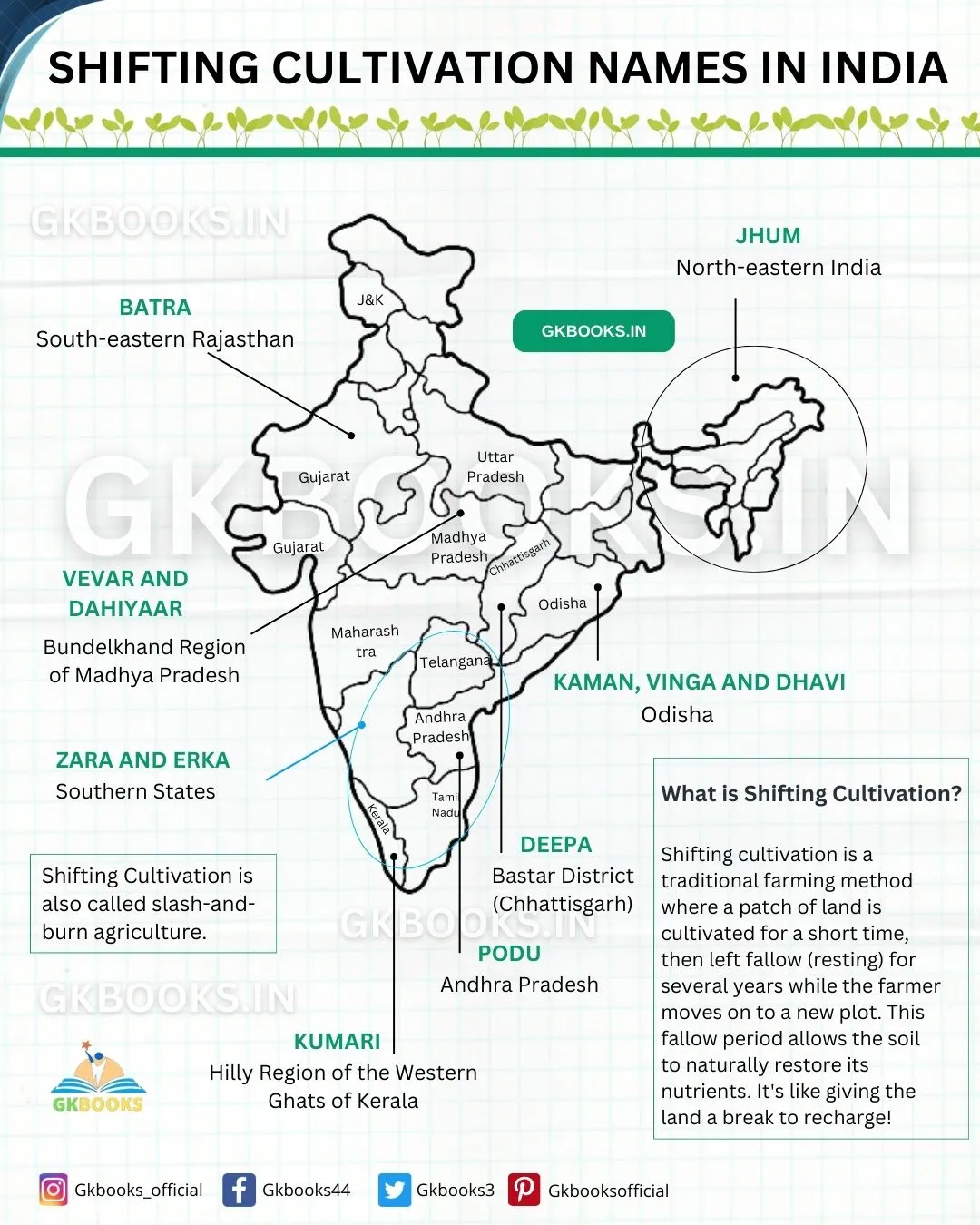

Different names of shifting cultivation in India

| Sl. No. | State/Region | Shifting Cultivation Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | North-eastern India | Jhum |

| 2. | Andhra Pradesh | Podu |

| 3. | Hilly Region of the Western Ghats of Kerala | Kumari |

| 4. | South-eastern Rajasthan | Batra |

| 5. | Bastar District (Chhattisgarh) | Deepa |

| 6. | Southern States | Zara and Erka |

| 7. | Bundelkhand Region (Madhya Pradesh) | Vevar and Dahiyaar |

| 8. | Odisha | Kaman, Vinga and Dhavi |

Shifting Cultivation Areas of Practice

Shifting cultivation, a method of farming, is widely practiced by many tribal communities in tropical regions across the world. It’s common in Mexico, Central Africa, tropical South and Central America, and Southeast Asia.

Different places have different names for it, like milpa in Mexico and Central America, Taungya in Myanmar, and Jhum in Bangladesh.

In India, it’s known as jhum cultivation and is found in small areas in the northeastern hilly regions, parts of the Western Ghats, and some parts of Central India.

In Madhya Pradesh, it’s called Poruh; in the Western Himalayas, it’s known as Bewar.

India’s Shifting Cultivation Map

Shifting Cultivation names in World

| Sl. No. | Country | Shifting Cultivation Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myanmar | Taungya |

| 2 | Sri Lanka | Chena |

| 3 | Thailand | Tamrai |

| 4 | Java, Indonesia and Malaysia | Ladang Humah |

| 5 | Philippines | Caingin |

| 6 | Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe |

Chetemini |

| 7 | Brazil | Roka |

| 8 | Venezuela | Konuko |

| 9 | Mexico and Central America |

Milya |

| 10 | Vietnam , Laos | Ray |

| 11 | Guatemala | Echalin |

| 12 | Madagascar | Tavi |

| 13 | Yucatan and Guatemala | Milpa |

| 14 | Mexico | Comile |

| 15 | Western Africa | Logan |

| 16 | Equatorial African Countries | Fang |

| 17 | Congo (Zaireriver Valley) | Masole |

| 18 | Japan | Karen |

| 19 | Sumatra | Diuma |

Shifting Cultivation: Cycle of Land and Crops

Shifting cultivation involves a cyclical process that utilizes the land’s natural fertility. Here’s a breakdown of its nature and methods:

Land Clearing and Planting

- A forest patch is often cleared by burning vegetation (slashing and burning). The ash acts as a natural fertilizer.

- This initial cultivation period benefits from the rich, virgin soil, leading to high crop yields.

Fallow Period (Land Takes a Break) and Regeneration

- After a few years, soil fertility declines, and weeds become problematic.

- The land is then abandoned and fallow for an extended period (usually longer than cultivation).

- During this fallow period, secondary forest growth takes over, restoring soil nutrients and suppressing weeds.

Starting Afresh

- After a sufficient fallow period (3 to 5 years or more), the land may be suitable for cultivation again.

- Farmers then shift to a new plot, repeating the cycle.

Key characteristics

- Uses simple tools like hoes and digging sticks.

- Relies on the natural regeneration of soil fertility.

- Primarily practiced for subsistence farming.

Benefits

- It can be sustainable if fallow periods are long enough.

- Reduces pest problems due to crop rotation.

Challenges

- It can lead to deforestation if not appropriately managed.

- Increased pressure on land due to population growth can shorten fallow periods, impacting sustainability.

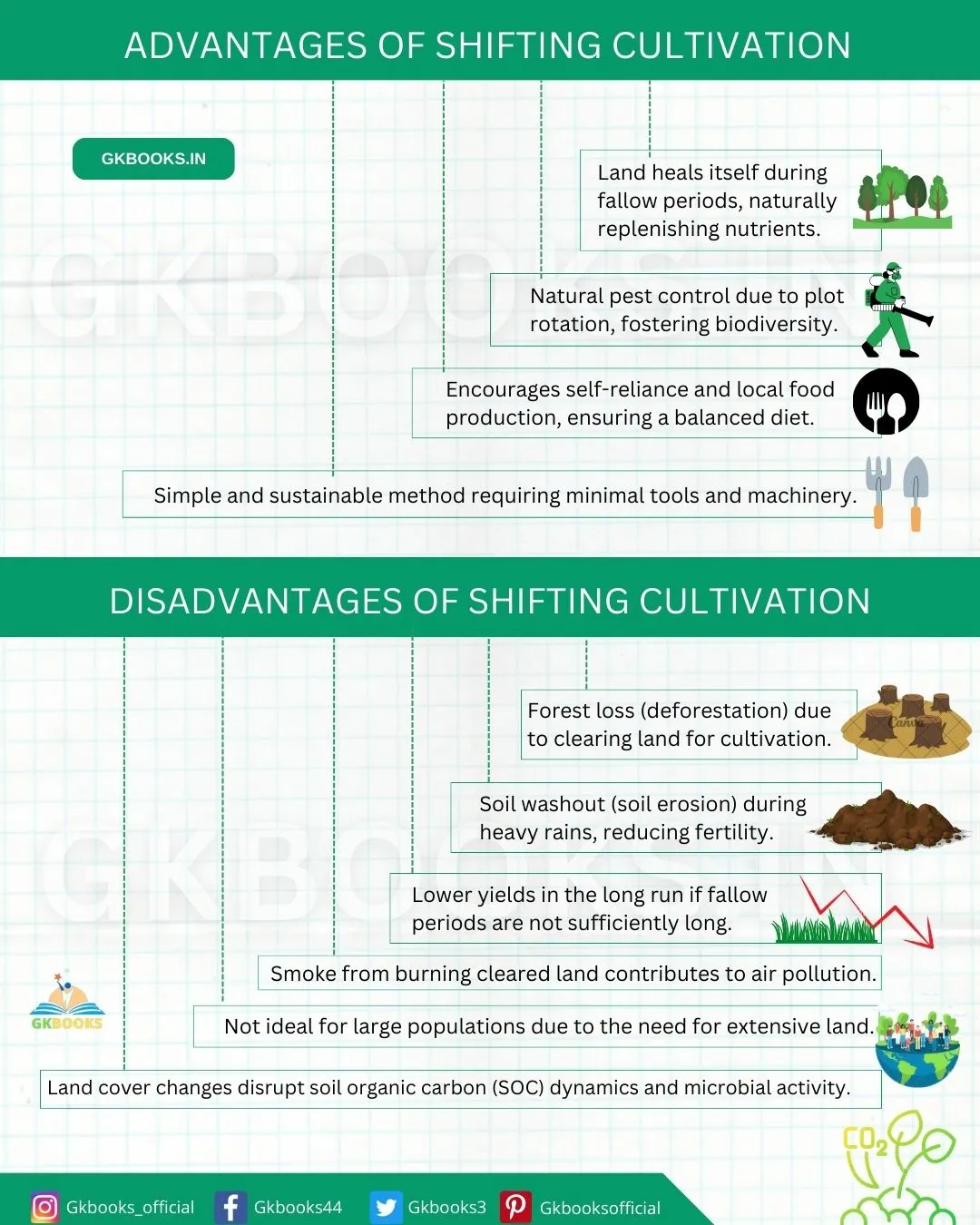

Advantages of Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation, a traditional practice in many parts of India, has some attractive advantages:

Land Heals Itself

Imagine cultivating a plot of land and then moving on to another one, letting the first rest for a few years. That’s what shifting cultivation does! During this fallow period, the land naturally replenishes nutrients like a hidden storehouse refilling its stocks. This keeps the soil fertile for future farming without needing chemical fertilizers.

Natural Pest Control & More Variety

When you keep moving cultivation plots, pests don’t get a chance to build up a permanent residence. This natural pest control helps farmers. Additionally, shifting cultivation allows various crops to be grown, creating a mix of plants that benefits insects and animals. This fosters a richer biodiversity in the area.

Self-reliance and local produce

Shifting cultivation allows communities to grow food and be self-sufficient. They cultivate various crops, ensuring a well-balanced diet and reducing dependence on outside suppliers.

Simple and sustainable

This farming method requires minimal tools and machinery, making it accessible to many communities. Since it relies on natural processes for regeneration, it can be sustainable if practiced with sufficient fallow periods.

It’s important to remember that shifting cultivation depends on having enough land for these fallow periods. With an increasing population, this can become a challenge.

Disadvantages of Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation, while having its benefits, also comes with some challenges:

Forest Loss (Deforestation)

Reducing trees to clear land for farming can lead to deforestation. It can disrupt the natural balance of the environment and reduce rainfall.

Soil Washout (Soil Erosion)

Heavy rains can wash away the fertile topsoil when land is left bare after cultivation. This will make it difficult for crops to grow in the future. Imagine soaking away the top, nutrient-rich soil layer, leaving less fertile land behind.

Lower Yields in the Long Run

The natural replenishment of nutrients in the soil takes time. If the fallow period (resting period) isn’t long enough, the land might not recover fully, leading to lower crop yields.

Not Ideal for Large Populations

Shifting cultivation requires a lot of land to allow for fallow periods. With a growing population, this method may not produce enough food for everyone.

Smoke from Burning (Air Pollution)

Burning cleared land can cause air pollution, harming people’s health and the environment.

loss of soil organic carbon

Land cover changes, particularly deforestation for jhum cultivation, plantations, and croplands, disrupt soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics and microbial activity.

This disruption leads to a significant loss of SOC, with studies in India reporting reductions between 21% and 60% across various agricultural and climatic regions.

Even within a state like Arunachal Pradesh, SOC concentration varies widely, ranging from 0.85% to 3.56% in the topmost 30 cm of soil, highlighting the impact of land-use practices on this vital soil component.

Examples of crops grown through shifting cultivation

Shifting cultivation often features root crops like tapioca, cassava, yams, but the specific crops grown can vary by region.

Farmers might also cultivate corn (maize), millet, upland rice, beans, bananas, and even some vegetables and fruits for their own consumption. These crops are mainly starchy staples that provide sustenance.

A Closer Look at Shifting Cultivation Practices in Nagaland

The major land use pattern in Nagaland is slash and burn cultivation, locally known as Jhum.

Traditionally, farmers would cultivate the land for two or three seasons and then leave it fallow for a period to allow the soil to recover nutrients.

This shifting cultivation system is the main source of livelihood for tribal people in Nagaland’s hilly areas.

However, population growth has increased pressure on land, leading to shorter fallow periods and potential negative impacts on soil fertility.

Jhum paddy still makes up a significant portion of rice cultivation in the state (around 56.5% of area and 49.26% of production).

Innovative Practices

There are also examples of innovative practices within Jhum cultivation in Nagaland:

Multiple cropping

Farmers in Wokha district practice intercropping, growing up to 40 different crops alongside paddy on the same plot.

Alder-based Jhum

In Khonoma village, farmers have adopted a system of planting Alder trees alongside crops. The Alder trees fix nitrogen in the soil, improving fertility, and also provide shade for cash crops like coffee and cardamom. This practice not only increases crop yields but also reduces soil erosion.

Cash Crops

While Jhum cultivation remains the dominant agricultural practice, some villages in Nagaland are adopting innovative techniques to improve sustainability and income.

One such example is the integration of cash crops with Jhum fields.

Farmers in Koio village under Chukitong block have begun cultivating large cardamom as a main cash crop alongside their traditional crops.

Fencing/Boundary Crops

To address the issue of decreasing fallow periods and soil fertility, the Koio village farmers also plant Tung trees (Aleurites fordii) along the boundaries of their plantations.

Additionally, passion fruit is grown as a fencing crop around the main cultivated area. This multi-cropping approach not only generates income from cash crops but also reduces pressure on the land by incorporating elements of permanent plantation and natural fencing.

This practice has been widely adopted by the farmers of Nagaland in recent years due to its ability to increase income and promote sustainable land use practices

Challenges

Around 73% of Nagaland’s economic activity revolves around agriculture, with slash-and-burn cultivation being the most common method, covering about 72% of the total cultivable area.

But as times change, so too do the challenges faced by the Naga tribes. With modernization creeping in, the delicate balance between tradition and progress hangs in the balance.

The practice of shifting cultivation contributes to an annual loss of about 88.3 x 106 tons of soil, while loss of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium results in up to 10.50 x 106 tons, 0.37 x 106 tons, and 6.05 x 106 tons respectively.

Population growth and the introduction of monoculture threaten the very essence of shifting cultivation, prompting the need for adaptation and conservation efforts.

About 100 or more tribes in the Northeast region depend on shifting cultivation for supporting their livelihoods, making it an integral part of the cultural and economic fabric of Nagaland.

Yet, amidst the shifting tides of change, one thing remains constant—the deep-rooted cultural significance of shifting cultivation to the Naga tribes. It is more than just a method of farming; it is a way of life, intricately woven into the fabric of their socio-cultural identity.

As Nagaland navigates the complexities of modernity while preserving its rich heritage, the Naga tribes stand resilient, drawing strength from their traditional knowledge and deep connection to the land. In their hands lies the future of shifting cultivation, a practice that has sustained them for generations and continues to shape the landscape of Nagaland.

Other indigenous farming system of Nagaland

| Farming System | States | Resource Conservation Method Practiced | Crop Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pani kheti/ WTRC | Nagaland, Manipur, Sikkim | Terracing, diverting water to the terrace from the hills | 2.5-3.0 t/ha |

| Zabo | Phek district of Nagaland | The farming landscape begins with forested areas in the uppermost hills, followed by centrally located animal sheds. Moving downhill, water harvesting reservoirs and tanks are situated, succeeded by cattle sheds. Finally, paddy fields and fish ponds, equipped with bunds to minimize runoff losses, occupy the lower areas. | 3.0-3.5 t/ha |

| Alder tree | Nagaland | Alder trees, reaching heights of up to 2 meters, contribute to soil fertility through their leaves and biomass, as this non-leguminous nitrogen-fixing tree enriches the soil. | 2.0-2.5 t/ha |

Characteristics of Shifting Cultivation

Characteristics of Shifting Cultivation include:

- After burning the forest, there’s no additional soil preparation before planting crops.

- Experienced elders usually select the plot to clear the forested area known as “ladang.”

- Hill slopes are preferred due to better drainage.

- Farming methods are basic, employing primitive tools like sticks and hoes without machinery or animal power. Manual labor is the primary means of clearing forests and cultivating crops.

- Starchy food crops like manioc, cassava, yams, tapioca, maize, millet, beans, and upland rice are commonly grown.

- Cultivated lands are typically small, around 0.5-1 hectare.

- Shifting cultivation essentially represents the migratory agriculture of indigenous tribes in tropical rainforests. While globally, it holds little economic significance, it serves as the primary livelihood for three-fourths or more of people living in tropical rainforests.

Is shifting cultivation intensive or extensive?

In the beginning, we already mentioned that shifting cultivation is an extensive practice. However, you may have a question: “Why is shifting cultivation so extensive?” Let’s discuss this in an easy and simple way.

Extensive farming emphasizes the utilization of small land areas with minimal inputs, aiming to maximize yield through the natural fertility of the soil. Here are some points to support this statement:

Resource Efficiency

- Shifting cultivation involves clearing and cultivating a small land area for a limited period.

- After a few years of crop production, the cultivators abandon the plot and move to a new one.

- This practice allows them to save resources, as they don’t need to maintain large, permanent fields.

- The virgin soil of the freshly cleared area provides abundant nutrients, leading to good yields initially.

Geographical Factors

Shifting cultivation is particularly prevalent in regions with specific geographical characteristics:

- Remoteness: Areas far from urban centers or markets often rely on this practice due to limited access to modern agricultural infrastructure.

- Undulating Terrain: Hilly or uneven landscapes (unavailability of large, fertile plains) make it challenging to establish permanent fields.

In such contexts, shifting cultivation becomes a practical choice for sustenance.

Natural Regeneration and Fallow Periods

- Fields are cultivated for relatively short periods (usually a few years).

- After cultivation, the land is allowed to recover naturally during fallow periods.

- During fallow, the vegetation regrows, enriching the soil and restoring fertility.

- Cultivators benefit from fallow fields for various purposes:

- Timber for fencing and construction

- Firewood

- Thatching material

- Ropes, clothing, and tools

- Medicinal plants

- Fruit and nut trees are often planted in fallow areas.

Environmental Adaptability

- Shifting cultivation is widespread in tropical regions of Central and South America, Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Southwest Pacific.

- Its survival over time suggests that it is a flexible and adaptive means of production.

- Despite its drawbacks (such as environmental degradation and soil erosion), it remains a viable choice for many communities.

In summary, shifting cultivation balances resource efficiency, geographical constraints, and natural regeneration, making it an extensive and enduring agricultural practice in certain contexts.

Extensive vs. Intensive Farming

The following table shows a comparison between extensive and intensive farming.

| Feature | Extensive Farming | Intensive Farming |

|---|---|---|

| Land Use | Large areas of land | Smaller areas of land |

| Resource Inputs | Low (fertilizers, pesticides, machinery) | High (fertilizers, pesticides, machinery) |

| Labor | Low labor intensity | High labor intensity, often supplemented by machinery |

| Yield per Unit Area | Lower yields per unit area | Higher yields per unit area |

| Sustainability | Can be more sustainable with proper fallow periods | Generally less sustainable due to potential for soil depletion and environmental impact |

| Examples | Shifting cultivation, pastoral grazing | Monoculture cropping (corn, soybeans), confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) |

| Suitability | Regions with abundant land and limited resources | Regions with limited land and high demand for food production |

Why is shifting cultivation no longer sustainable?

Shifting cultivation, once considered a sustainable form of agriculture, is now primarily viewed as unsustainable due to several reasons:

- Deforestation: Shifting cultivation involves felling trees for temporary cultivation, contributing to deforestation.

- Soil Erosion: The practice often leads to soil erosion.

- Loss of Biodiversity: The change in land use can result in a loss of biodiversity.

- Population Pressure: With increasing population pressure, the productivity of shifting cultivation declines.

- Shortening of Fallow Periods: The periods of fallow, which are crucial for soil recovery, are getting shorter.

- Non-availability of Alternative Land: There needs to be more alternative land for shifting cultivation due to various factors.

Moreover, efforts to replace shifting cultivation with settled agriculture have led to second-generation issues such as loss of dietary diversity, declining ecosystem services, and compromised tenurial security, leading to landlessness and poverty. Therefore, the sustainability of shifting cultivation is now being questioned.

How does shifting cultivation affect the economy of India?

Shifting cultivation plays a complex role in the Indian economy, particularly in the northeastern states. Here’s a breakdown of its impact:

Positive Impacts

- Livelihoods: For many, especially in Mizoram, Jhum is the primary source of income and a way of life. A significant portion of the rural population (around 54%) relies on it for subsistence.

Negative Impacts

- Decreased Productivity: Over time, crop yields under Jhum cultivation have declined. This means less income and less food security for those who depend on it.

- Poverty: Jhum’s economic viability is decreasing, leading to a higher poverty rate in rural areas than those cultivating cash crops.

- Uneconomical Land Use: The practice limits how intensive land can be used, hindering overall economic productivity.

Shifting Cultivation’s Future

Studies suggest that Jhum’s long-term sustainability could be improved. Here are some potential solutions:

- Transition to Cash Crops: Shifting from subsistence crops grown under Jhum to higher-value cash crops could improve rural incomes.

- Sustainable Practices: Converting Jhum plots into permanent cultivation through terracing could be a solution, but it requires careful planning and support for farmers.

Shifting cultivation provides a vital source of income for some, but its limitations and negative environmental impacts are becoming more apparent. Finding ways to transition to more sustainable practices and alternative income sources will be crucial for the long-term economic well-being of these communities.

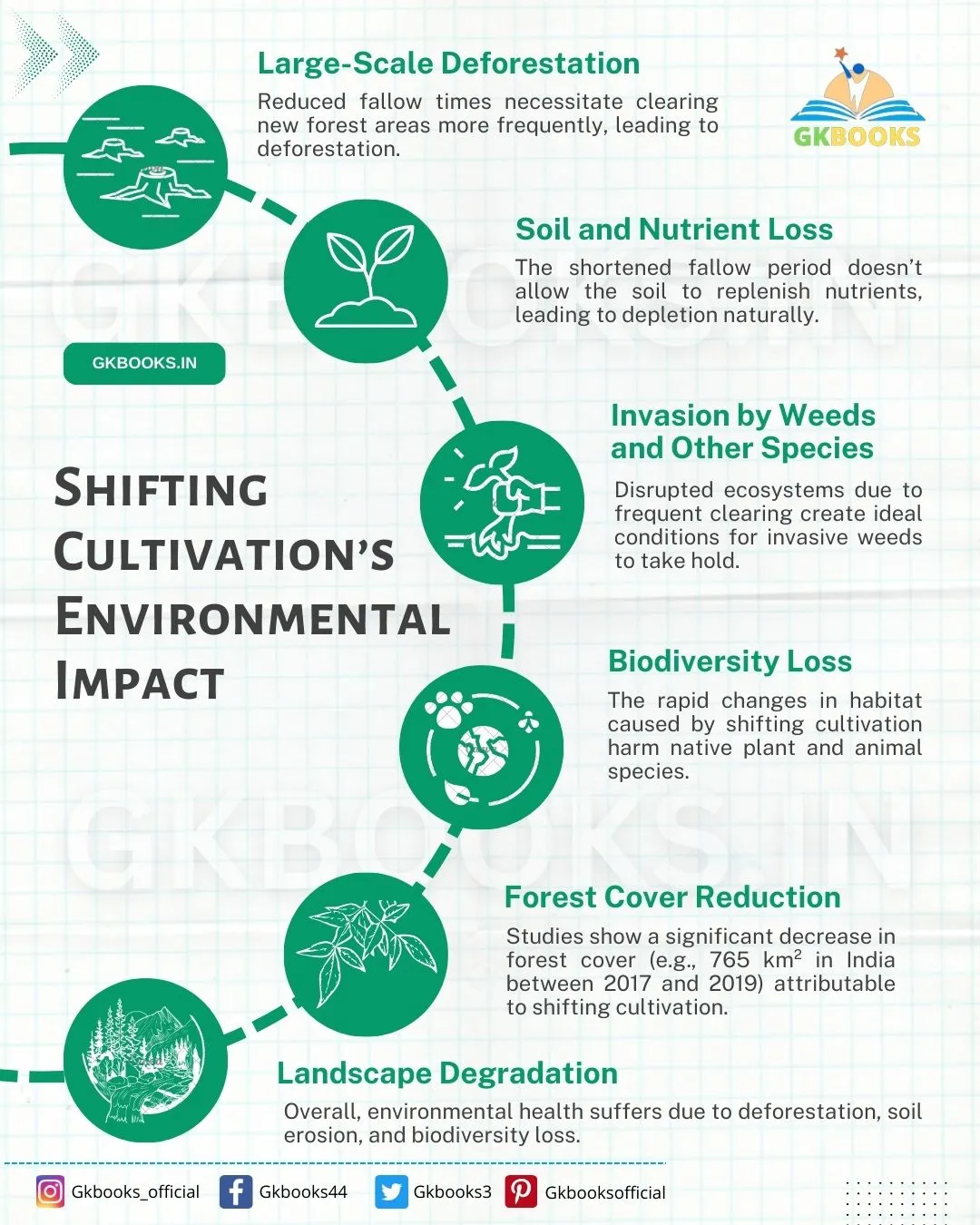

Shifting Cultivation’s Environmental Impact in India: A Two-Sided Coin

Shifting cultivation, also known as Jhum or Jhuming agriculture, plays a significant role in India, particularly in the northeast. However, its environmental impact is a cause for concern.

Traditional Practices vs. Modern Pressures:

Traditionally, shifting cultivation with extended fallow periods (15-20 years) can be sustainable. However, population growth has shortened these cycles to just 2-3 years, leading to several environmental issues:

- Large-Scale Deforestation: Reduced fallow times necessitate clearing new forest areas more frequently, leading to deforestation.

- Soil and Nutrient Loss: The shortened fallow period doesn’t allow the soil to replenish nutrients, leading to depletion naturally.

- Invasion by Weeds and Other Species: Disrupted ecosystems due to frequent clearing create ideal conditions for invasive weeds to take hold.

- Biodiversity Loss: The rapid changes in habitat caused by shifting cultivation harm native plant and animal species.

- Forest Cover Reduction: Studies show a significant decrease in forest cover (e.g., 765 km² in India between 2017 and 2019) attributable to shifting cultivation.

- Landscape Degradation: Overall, environmental health suffers due to deforestation, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss.

Conclusion

While shifting cultivation is a traditional practice, its current form has severe environmental consequences. Finding a balance between supporting livelihoods and implementing sustainable practices is crucial for the future.

Previous Year Questions on Shifting Cultivations

Q1. Which methods do not help conserve soil fertility and moisture? (SSC Section Officer (Audit) 2006)

[A] Contour ploughing

[B] Dry farming

[C] Strip cropping

[D] Shifting Agriculture

Q2. “Slash and Burn agriculture” are the name given to: (SSC Section Officer (Commercial Audit) 2007)

[A] method of potato cultivation

[B] process of deforestation

[C] mixed farming

[D] shifting Cultivation

Q3. Jhumming is shifting agriculture practiced in: (SSC (10+2) Level Data Entry Operator & LCD 2011)

[A] North-eastern India

[B] South-western India

[C] South-eastern India

[D] Northern India

Q4. At the time of independence, predominantly India practiced: (SSC CGL Tier-I Re-Exam. (2013) 2014)

[A] Subsistence agriculture

[B] Mixed farming

[C] Plantation agriculture

[D] Shifting Agriculture

Q5. Leaving agricultural land uncultivated for some years, known as: (SSC GL Tier-I Exam. 2014)

[A] Intensive farming

[B] Fallow

[C] Shifting Cultivation

[D] Subsistence farming

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation is an agricultural system in which plots of land are cultivated temporarily and then abandoned. At the same time, post-disturbance fallow vegetation is allowed to grow while the cultivator moves on to another plot freely.

“Forest Eaters”

The humid tropics of Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America.

Northeast India, like Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, and other parts of India like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and Odisha.

Dahiyaar or Dahiya is a shifting cultivation practiced by Baiga tribes. Baiga means sorcerers. Baiga tribes mainly live in Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh.

Humah shifting cultivation is practiced in Indonesia.

Milpa and Ladang are different names for shifting cultivation, and they are practiced in Yucatan, Guatemala, and Java, Indonesia, respectively.

Major Source:

- Wikipedia

- NCERT Class 10 Social Science – Chapter 4- Agriculture

- Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry

- International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications/ Department of Anthropology, NEHU, Shillong

Explore More on Indian Geography: